At 3:15 pm on October 4, the S&P 500 was at 1081.89. By 4:oo pm it finished at 1123.95, up 3.89% in forty-five minutes. To put that in perspective, the market was in the 1081 range in October 1998. So, in a span of thirteen years the market was completely flat, and in forty-five minutes investors suddenly realized that they were wrong about the previous thirteen years? (I know a lot happened in the interim, but let’s abstract for a minute for some perspective.) Even if you add in the dividends that you would have received, you could still go all the way back to December 1999 to find a market level that delivered a zero return up until 3:15 pm on October 4.

One week later and the market is up over 12% since 3:15 pm on October 4 (as I write this). Based on what? As best as I can, tell the reason behind the forty-five minute swing on October 4 was, 1. a rumor that leaders in Europe had; 2. a plan to make; 3. a plan to fix the European debt crisis. The reason for the over-8.5% spike since October 4 is that the rumor was true: Sarkozy and Merkel are planning to make a plan. The details will be out soon; just you wait and see.

For even more perspective on Europe’s looooong-term problem, read Michael Lewis’s excellent Boomerang: Travels in the New Third World. You can find it in the Value Investing Bookstore tab above.

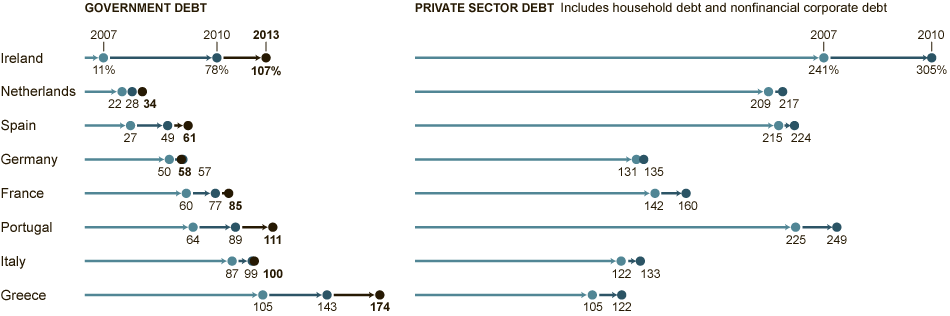

All other economic and financial news since 3:15 pm on October 4 has been mixed at best and slightly worrisome at worst. There are two things on which I think investors must place more weight: First, public and private debt-to-GDP levels have exploded to record levels in advanced economies. Given a 12% spike in equity prices in one week, market players must be expecting much more economic growth than they did before October 4, so the other item on which investors must place more weight is Rogoff and Reinhart’s conclusion to their paper, A Decade of Debt (http://papers.nber.org/papers/w16827):

The sharp run-up in public sector debt will likely prove one of the most enduring legacies of the 2007-2009 financial crises in the United States and elsewhere. We examine the experience of forty four countries spanning up to two centuries of data on central government debt, inflation and growth. Our main finding is that across both advanced countries and emerging markets, high debt/GDP levels (90 percent and above) are associated with notably lower growth outcomes. Much lower levels of external debt/GDP (60 percent) are associated with adverse outcomes for emerging market growth. Seldom do countries grow their way out of debts. The nonlinear response of growth to debt as debt grows towards historical boundaries is reminiscent of the―debt intolerance phenomenon developed in Reinhart, Rogoff and Savastano (2003). As 44 countries hit debt intolerance ceilings, market interest rates can begin to rise quite suddenly, forcing painful adjustment.

For many if not most advanced countries, dismissing debt concerns at this time is tantamount to ignoring the proverbial elephant in the room. So is pretending that no restructuring will be necessary. It may not be called restructuring, so as not to offend the sensitivities of governments that want to pretend to find an advanced economy solution for an emerging market style sovereign debt crisis. As in other debt crises resolution episodes, debt buybacks and debt-equity swaps are a part of the restructuring landscape. Financial repression is not likely to also prove a politically correct term—so prudential regulation will provably provide the aegis for a return to a system more akin to what the global economy had prior to the 1980s market-based reforms.

The process where debts are being placed at below market interest rates in pension funds and other more captive domestic financial institutions is already under way in several countries in Europe. Central banks on both sides of the Atlantic have become even bigger players in purchases of government debt, possibly for the indefinite future. For the United States, fear of currency appreciation continues to drive central banks in many emerging markets to purchase U.S. government bonds on a large scale. In other words, markets for government bonds are increasingly populated by nonmarket players, calling into question what the information content of bond prices are relatively to their underlying risk profile—a common feature of financially repressed systems.

The data: